The Ghost Runner: John Tarrant’s story of triumph and tragedy

[ad_1]

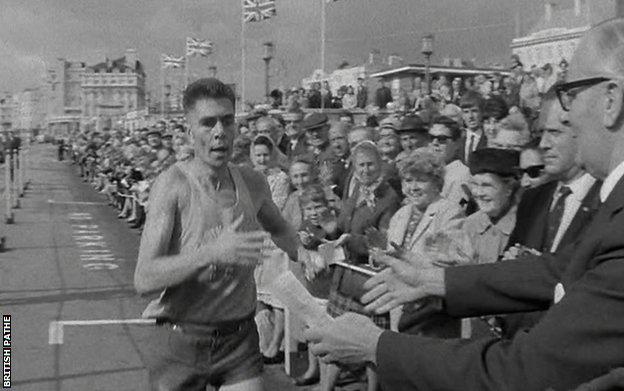

Easter Monday, 1957. A heavy gloom settled over Doncaster as crowds gathered for the half marathon ending in Sheffield.

The starting area was swarming with race stewards, many carrying a photo of the man they had been instructed to stop at all costs.

To the officials he was a gatecrasher, a scoundrel who must be prevented from racing. To almost everybody else, he was a downtrodden champion battling injustice.

Runners now pressed forward as the start time neared. The local mayor raised his arm to the clouds and with the crack of his starting pistol, the race was under way. Seconds later, another sound ripped through the air.

A spectator huddled beneath a long coat and a large hat had thrown his disguise clear, revealing his racing attire as he jumped, numberless, into the race. The spectators thundered their approval, and the stewards flailed as he skipped around them to join the runners disappearing down the road.

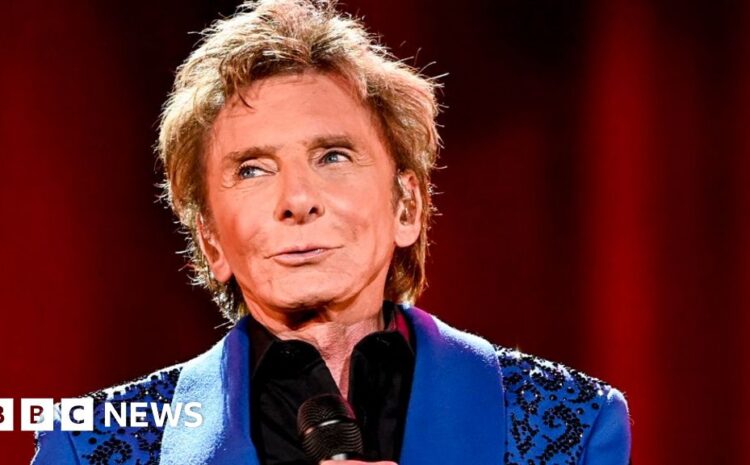

John Tarrant’s sporting career fused triumph and tragedy. One of Britain’s finest long-distance athletes of the late 1950s and 1960s, he ran multiple world records but was denied his full share of glory by the stubborn authorities who banned him from racing.

Tarrant wouldn’t let them stop him. He was a dogged and brilliant competitor. A numberless outlaw. They called him the Ghost Runner.

Born in London in 1932 to parents John and Edna, Tarrant lived his early years in poverty but they were loving nonetheless. His brother Vic arrived in 1935 and, for a time, life progressed as childhood should.

However, in 1940, with their mother’s health failing and their father called up to man London’s anti-aircraft batteries, the brothers were sent to Lamorbey Children’s Home in Kent. There they would remain for the next seven years.

A stark setting at the best of times, life at Lamorbey was intensified by the terror of the Blitz. It got worse for the Tarrant boys. Two years later, their mother Edna died from tuberculosis.

It wasn’t until August 1947 that their father collected them. Recently remarried and with a new-born baby, he moved the family to the Derbyshire town of Buxton, on the edge of the Peak District.

In this beautiful and savagely hilly landscape, the young Tarrant took to running with a stubborn zealousness that quickly consumed him. It became his catharsis. Soon he was known for a capacity to push himself further than most would even consider attempting.

“He used running as his psychological help,” says Nicola Tyler, who is chair of the Ghost Runners running club in Hereford and was trained by Tarrant’s brother Vic for many years.

“After that kind of childhood, of course, you’re going to be angry and rebellious.”

In 1949, aged 17, Tarrant took up boxing and participated in Buxton’s inaugural fight night. He competed a further seven times over two years, earning himself a total of £17 – worth about £400 today. Full of heart but lacking much prowess, he quit the sport in 1951, blissfully unaware how damaging his inglorious stint as a professional boxer would turn out to be.

Various manual labour jobs came and went, usually discarded in search of more time to run. Even on honeymoon after his marriage to Edith Light in 1953, Tarrant took along his training gear. With his weekly mileage quickly climbing, he’d set his sights on the Olympics – but first he needed to join a club.

British athletics in the 1950s was governed according to a moral standard supposedly inspired by the Ancient Greeks but which stank of inequality and exclusion.

Held up as a symbol of integrity, amateur sports were not to be sullied by those who had ever received payment for competing. It was a rule which, as Britain clawed itself out of the wreckage of World War Two, disproportionately affected the poor.

Most got round the issue by simply not disclosing any earnings, but Tarrant felt it only right to formally declare his boxing exploits when applying to join the Amateur Athletic Association (AAA).

Two weeks later a letter arrived returning his six shillings subscription fee. He was informed that he was now banned from amateur athletics for life – including events such as the de facto British championships and trial races for Olympic selection. He bombarded officials with replies, pleading his case, but to no avail.

Driven by a burning sense of injustice, Tarrant and his brother Vic concocted a plan. Why not simply run unregistered in the AAA races? Not only would it allow him to compete, it might even spark a debate within the media.

Things began badly, however. Various misfortunes meant they arrived late to race starts in Macclesfield and Leeds. Nothing was left to chance when Tarrant arrived in Liverpool for the city’s marathon on 11 August 1956.

After discreetly changing, he wound his way through crowds to the start line, the only man without a number.

As the race began, he attached himself to the leading pack before bursting clear after 11 miles. Rarely one for finesse or race strategy, Tarrant would come with one gear – full throttle – and a relentless, almost reckless approach to competition.

In this case, his rookie exuberance held up until mile 19 when he was caught by the chasing pack. His body racked with exhaustion and cramp, he slumped to the ground two miles from the finish.

Despite this disappointment, Tarrant’s endeavours in Liverpool had caught the eye. After he gave an impromptu press conference before boarding the train back to Buxton, a new nickname spread, courtesy of the Daily Express: the Ghost Runner.

Over the coming years he would repeat the trick again and again, gatecrashing races across the country. As media attention and public interest grew, he would frequently need to slalom through a pack of stewards desperately trying to catch him at the start of races. When he won, which he began to do frequently, his success would be met either with eerie silence or a public scolding over the loudspeakers.

And yet, despite the official line, Tarrant had become a hugely popular character who would be cheered on by hundreds, sometimes thousands, of spectators.

“Tarrant was an unattractive human sledgehammer of a runner but with an indomitable spirit,” says Bill Jones, author of The Ghost Runner – The Tragedy of the Man They Couldn’t Catch.

“He ticked all the right boxes in the 1950s of the young, angry, working-class hero.”

In 1958 a letter finally arrived from the AAA informing Tarrant that his ban had been overturned. Although exact reasoning was not given, the decision came just one month after Harold Abraham – 100m gold medallist at the 1924 Paris Olympics and influential member of various athletic committees – wrote an article highlighting crude deficiencies in the case against Tarrant.

But elation quickly gave way to renewed resentment. It emerged that while Tarrant had been cleared to run in British races, he would remain banned from representing his country internationally.

His dream of running at the Olympics crushed, Tarrant nonetheless went on to dominate the domestic scene, establishing himself as one of the best long-distance runners in Britain.

The 1960s saw him win a blizzard of events, including the London to Brighton 54-mile race twice, the Liverpool to Blackpool 48-mile race three times, and the Exeter to Plymouth 44-mile race five times. He set world records at 40 and 100 miles – to go with his Territorial Army 110-mile march record set in 1959.

But just as in Liverpool, there were also numerous races where he failed to finish, often because of the stomach complaints that plagued his career. On any given day he could reign supreme or be seen staggering away, arms clutched around his abdomen.

By the mid-1960s, a sense of dissatisfaction was setting in. The desire for a new challenge, and to compete around the world, now consumed Tarrant.

South Africa’s Comrades Marathon, linking Durban and Pietermaritzburg, describes itself as the oldest ultra-marathon in the world, stretching for about 55 miles through KwaZulu-Natal province.

In 1968 it was still an exclusively white male race. Black competitors, and women, were formally excluded. But a few still raced nonetheless.

Tarrant was among the interlopers that year, after South African officials rejected his application to run following pressure from the AAA. For the first time in his life, the Ghost Runner joined other phantoms on the fringes.

A fourth-place finish was more than respectable, but below par in the eyes of Tarrant. He returned the following year, this time while entertaining the idea of emigrating.

His second Comrades looked like being a complete disaster but was salvaged by a gutsy display that saw him finish 28th after suffering debilitating stomach issues along the way – far beyond what had seemed possible at halfway.

Tarrant took on the Comrades twice more, in 1970 and 1971, failing to finish both times. His dream of conquering the gruelling contest remained unfulfilled, but it did lead to arguably his defining moment.

During the 1969 Comrades, whispers began circulating about a new, multi-ethnic race that would be open to all. As the date neared, it remained unclear whether it would go ahead and how many – if any – white runners would compete.

On the morning of 6 September 1970, as runners gathered in Stanger for the Gold Top Marathon, a 50-mile race to Durban, there was a solitary white competitor: John Tarrant. He won it in five hours 43 minutes.

The following year the number of white runners doubled, with a 15-year-old Dave Upfold, who had begun training with Tarrant occasionally, also competing.

“We were expecting the police, maybe even the army,” says Upfold.

“In 1971 we simply weren’t allowed to compete together, but there was nothing.

“It was the start of the acceptance that people of colour could run, and run well.

“By 1975, the Comrades was fully integrated with women and all ethnicities taking part, and Tarrant was certainly part of that.”

Tarrant also won that 1971 Gold Top, improving his time by three minutes, but serious problems were emerging.

Six weeks later he suffered a massive haemorrhage and woke up vomiting blood. Doctors failed to diagnose a cause so he was discharged from hospital and soon back running over 100 miles a week. All was clearly not well, but quite remarkably, one final epic remained.

On 23 October 1971, 12 runners, including a 39-year-old Tarrant, began the Radox 100 Mile track race held at the Uxbridge Sports Centre in west London.

By mile 60 he was struggling badly, alternating between walking and slowly jogging, with race leader Ron Bentley 17 minutes ahead. The once imperious ghost was fading dramatically and few held much hope of him finishing, let alone winning.

But as he had done time and time again, Tarrant dug deep into what propelled him and battled on. Slowly the gap began to shrink until he was just two laps behind Bentley. Suddenly the unthinkable seemed possible.

In the end, thanks to a late burst, Bentley finished 14 minutes ahead of second-placed Tarrant, who ended his last major race in an appalling condition – his lips blue, froth seeping from his mouth as he collapsed at the finish line. Eventually his brother Vic, his steadfast rock throughout the years, shepherded him into a waiting car and the Ghost Runner disappeared. Forever.

“It was Tarrant’s greatest race,” said race organiser Eddie Gutteridge in Jones’ book, The Ghost Runner.

“He was in bits, mortally ill as we now know. God knows how he did it. It moved you to be there.”

Two years later Tarrant was finally diagnosed with stomach cancer. He died on 18 January 1975, aged just 42.

Today, in his adopted home of Hereford, close to the town’s running club, stands a sculpture in his honour – created, somewhat symbolically, by vulnerable teenagers living in a residential home nearby.

“He believed in fairness. Fairness for himself, fairness for everybody, equality for all,” says Upfold. “Nearly 50 years after his death, people still remember the name John Tarrant.”

Tyler adds: “He wasn’t allowed to officially win, but he was still determined to show people what he could do.

“It wasn’t just about running. It was about overcoming adversity and believing in yourself. That’s why people still love this story.”

[ad_2]

Source link