Hidilyn Diaz: From accusations of anti-government plot to historic Olympic gold

[ad_1]

It was the third day of the Tokyo 2020 Olympics and Hidilyn Diaz’s world was about to change forever. Five years of preparation, pain and patience came down to one crucial moment.

The room was quiet as she approached the weightlifting platform for her final lift in the women’s 55kg category. China’s Liao Qiuyun was in the lead after successfully raising 126kg.

Diaz looked confident. Focused. She spoke the personal mantra that had carried her through the competition so far: “Chest out. Deadlift. One motion.” She had one final shot at making history for her country with the Philippines’ first Olympic gold.

Seconds later, with 127kg of metal raised perilously above her head, emotion rushed across her face as the buzzer sounded to confirm a clean lift. Aged 30, she had achieved the victory she had dreamed of for so long.

It had been a difficult journey for Diaz, for many reasons. Because of the attitudes she encountered growing up. Because she had found herself locked down in a foreign country for a year over Covid. And because in 2019 she was named an “enemy of the state”.

The Philippines first took part in the Olympics in 1924, sending just one athlete to Paris – David Nepomuceno, a sprinter.

The woman who won the Philippines’ first Olympic gold, ending a 97-year dry spell, was born in 1991 in Zamboanga City, a city of almost one million people in the country’s south. One of six siblings, Diaz’s father earned a living providing short-haul transport on a tricycle, while her mother was a full-time housewife.

She was 11 when a cousin introduced her to weightlifting, much to her mother’s dismay.

“My mum told me, ‘No one will like you when you’re older. That sport is for men. You’ll get big muscles and you won’t get pregnant,'” Diaz says.

“I still did it because I enjoyed it. But later she started supporting me, when she saw how much I enjoyed it and the benefits it had, like my high-school scholarship.”

Diaz was gifted. Within six years she was competing on the biggest stage of all. Aged just 17, she went to the 2008 Olympics in Beijing, where she finished second-last in a field of 12.

At London 2012 she was her country’s flagbearer, but the Games ended in disappointment as she failed with three attempts to lift her opening weight. Still, everybody had high hopes for the future.

Now combining an athletic career with service in the Philippine Air Force, it was at Rio 2016 that Diaz made her big breakthrough with silver – the first Olympic medal won by a Filipino female.

Before Tokyo 2020, she had further distinguished herself on the international stage with Asian Games gold in 2018 and bronze at the 2017 and 2019 World Championships.

But one year before the Games in Japan were due to take place, there was a twist nobody saw coming.

In 2019 Diaz was accused of being involved in a plot to oust the country’s president Rodrigo Duterte.

Elected in a 2016 landslide win on the back of hard-line promises to tackle crime and corruption, Duterte, 76, has attracted intense controversy for a bloody drug war and a string of remarks deemed offensive or sexist by many observers.

In June, the International Criminal Court’s chief prosecutor called for an investigation into suspected crimes against humanity during the deadly drugs crackdown directed by his government.

The accusation levelled at Diaz in 2019 came as Salvador Panelo, the presidential chief legal counsel at the time, presented details of an alleged network of “enemy” individuals and organisations the government claimed were involved in an “attempt to discredit the Duterte administration”. They called it the “Oust Duterte” matrix.

It included members of opposition political parties, celebrities and journalists, including the outspoken Duterte critic Maria Ressa, joint-winner of the 2021 Nobel Peace Prize.

It has since been suggested that Diaz’s inclusion came down to the fact she was being followed on social media by blogger Rodel Jayme, who was arrested in 2019 for allegedly sharing online videos claiming Duterte and his allies were involved in the very drug trade he claimed to be stamping out.

Diaz at first found it all bemusing. Then she began to receive abuse from Duterte supporters on social media. Then those close to her were targeted.

“I was in training when someone messaged me about it,” she says.

“They were saying bad things to my dad. I was shocked but I got more hurt when they involved my family. After that, I started crying.

“People were messaging me on social media, saying bad things and bashing me, but I didn’t even know what was happening. I don’t know what’s going on and they were bashing me about something that isn’t even true.

“I was just so busy preparing myself for the Olympics. It was a hard time, but I was able to overcome it with the people who believed in me.”

All of this took a serious toll on Diaz’s mental health. And then came the pandemic.

As borders shut and flights were cancelled around the world in early 2020, Diaz and her team found themselves stranded in Malaysia, where she was training, with no indication as to when they could return home.

Using the limited resources available in their rented accommodation in Kuala Lumpur, Julius Naranjo, Diaz’s fiancé and coach, improvised a new programme. They used the parking area as their cardio space and hung water bottles off bamboo sticks to serve as makeshift weights.

“Anxiety was so high,” Diaz says. “We didn’t even know what lockdown was. We thought it would only last for two weeks. I’m from the Philippines. My coaches are from Guam and China. We didn’t know anyone in Malaysia.”

It soon became clear the Tokyo Games would have to be postponed.

“An additional 12 months for me [in training]… I felt like I couldn’t do it,” Diaz says.

“When I talked to our sports psychologist I would feel like crying and would tell them how I was feeling. They just said take it day by day. Control the things I can control because I can’t control anything else.”

The following summer it all paid off.

“I already knew I would win – I expected it,” Diaz says. “You have to claim before you perform. I have to believe that I can do it.

“When I was there in the competition, I’m like: ‘This is my day. I believe in God, I believe in my team, the last one is I just need to believe in myself.'”

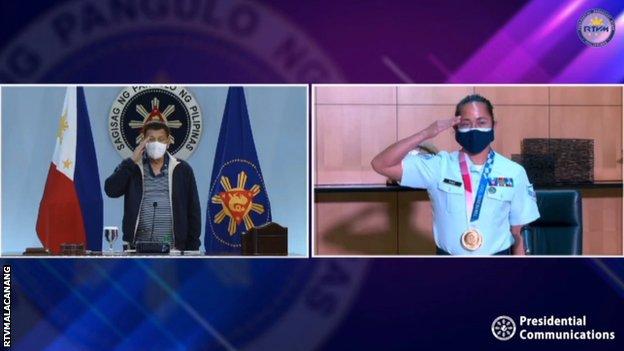

When she returned home from Japan with her country’s first Olympic gold, she was congratulated by the same president she had been accused of plotting against. When Duterte spoke with her, he did not explicitly mention the accusation. But he did encourage Diaz to “let bygones be bygones”.

Diaz adds: “There was a video call. Then after that, we met him in the [Malacanang] Palace. We were happy and I think everyone’s happy with the achievement by the Filipino athletes in the Tokyo Olympics.”

Claims of a conspiracy to oust Duterte were never substantiated. He remains in power. Although he is not eligible to stand in May’s presidential elections because the constitution bars him from a second term, his daughter Sara is currently frontrunner for vice-president. The leading presidential candidate is the son of Ferdinand Marcos, the brutal dictator who was removed from power in 1986.

Diaz admits nothing could have prepared her, or her fiancé and coach Naranjo, for how their lives would change.

She became a national hero overnight. She was also to be awarded a handsome sum by the Philippine government – a law passed by the previous administration guarantees PHP 10 million (approximately £150,000) to any Filipino who takes home Olympic gold.

“The competition was Monday, it sunk in that I had won on Saturday,” Diaz says. “I felt like in those five days, I’m in the clouds. I’m like: ‘Is this really the truth? Is this reality? I’m the first gold medallist? Me? Wow… Just, wow.”

Big endorsement deals were waiting, and her public profile has since rocketed. She appears in TV ads, social media campaigns and on billboards. In 2021, the Philippine Post Office honoured her with her own set of stamps.

And with the platform she now has, Diaz intends to help break barriers and inspire other young girls to pursue their dreams.

“I grew up insecure with myself because I got into sports,” she says. “There’s this mindset about women, a stereotype, so it’s good that girls have someone [different] to look up to.

“They have someone to look to and say: ‘Big sister Heidi did it. I can do it too.'”

[ad_2]

Source link