Feds suspend Flaming Gorge water releases meant to boost Lake Powell

[ad_1]

CNN

—

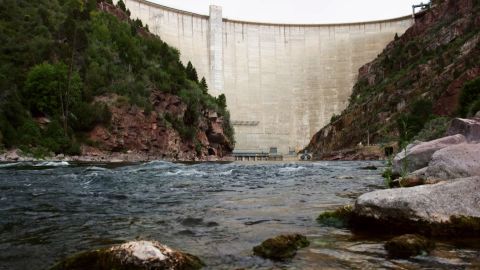

Starting Tuesday, the US Bureau of Reclamation will suspend extra water releases from Utah’s Flaming Gorge reservoir – emergency measures that had served to help stabilize the plummeting water levels downstream at Lake Powell, the nation’s second largest reservoir.

Federal officials began releasing extra water from Flaming Gorge in 2021 to boost Lake Powell’s level and buy its surrounding communities more time to plan for the likelihood the reservoir will eventually drop too low for the Glen Canyon Dam to generate hydropower.

Lake Powell in late February sank to its lowest water level since the reservoir was filled in the 1960s, and since 2000 has dropped more than 150 feet.

But Reclamation Bureau officials acknowledged late last summer that Flaming Gorge was also running precariously low.

The decision to suspend the monthly water releases, which were slated to continue through April, comes in the wake of a winter that has brought well above-average snowfall and precipitation in much of the West, which state and federal officials are hoping will buy them some more time as they scramble to come to an agreement on significant water usage cuts from the Colorado River Basin.

The suspension of Flaming Gorge releases was initially requested by four states in the upper Colorado River Basin – Utah, Colorado, Wyoming and New Mexico. The system is like a water loan program from Flaming Gorge to Lake Powell “in times of crisis,” said Chuck Cullom, executive director of the Upper Colorado River Commission.

“With snowpack in the upper Colorado River system running upwards of 130% of the 30-year median, we have a unique opportunity – perhaps once-a-decade opportunity – to repay the loan,” Cullom told CNN. “Aridity is our present and future and we’re trying to adapt to this unique set of circumstances.”

As of last week, snowpack across much of the upper Colorado River Basin was between 120 and 140% of normal. And the Arizona state climatologist’s office recently reported that 2023 ranks in the top five years for the amount of water it expects to get out of the snowpack as it melts.

“We’re well ahead of where we need to be from a snowpack perspective,” said Paul Miller, a hydrologist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Colorado Basin River Forecast Center. “We’re very optimistic right now that we’re in a good spot. This year is a good year to try and save water, to try to conserve water as best as we can; we have a lot of space in our reservoirs.”

While agreeing to the suspension, officials from three lower basin states – Arizona, California and Nevada – have cautioned that stakeholders should wait to see how good the rest of the winter and spring precipitation is before ruling out any future Flaming Gorge releases to help prop up Lake Powell.

“We do need to see what the runoff is going to be; I’m hoping it’s going to be good,” said Arizona’s top water official Tom Buschatzke. Still, Buschatzke cautioned that hydrology can taper off in the spring; with the nation’s largest reservoirs so precipitously low, one year is not going to make enough of a difference.

“Even really good hydrology – if it tracks the way it’s been tracking – it’s going to buy us 6 months or a year at most,” he said. “It’s not going to stabilize the system in any meaningful way.”

After months of negotiations with farmers, tribes and cities, federal officials will soon announce the results of its first round of voluntary short-term water cuts in the Southwest, paid for with part of the $4 billion in drought relief funds that were passed in the Inflation Reduction Act.

Top officials at the Department of Interior and Reclamation recently told a group of Western senators that they expect to be able to save up to 10 feet of elevation in Lake Mead – or about 650,000 acre-feet of water. That water savings will cost about $250 million of the total $4 billion, Democratic Sen. Mark Kelly of Arizona, who was in the meeting, told CNN.

Much of this water savings will come from farmers fallowing fields for one to three years. The longer a farmer agrees to fallow fields, the more money they get: A one-year agreement gets $330 per acre-foot, two years gets $365 per acre-foot, and three years gets $400 per acre-foot, according to the Interior Department.

Agreements to fallow fields have already been signed, but Reclamation is still negotiating a substantial part of the overall deal with California farmers – meaning the final amount of water savings could ultimately change.

It was not immediately clear how much the Biden administration is paying individual farmers to fallow their fields.

Kelly noted that while 10 feet of water “might not sound like a lot,” it would boost Lake Mead above the Tier 2 water cuts threshold, which went into effect in January. The Tier 2 shortage meant that Arizona, Nevada and Mexico had to reduce their Colorado River water usage, with Arizona facing the largest cuts – 592,000 acre-feet – or approximately 21% of the state’s yearly allotment of river water.

The fallowing measures could leave enough water in Lake Mead this year to prevent another Tier 2 shortage next year.

Kelly said that additional portions of the $4 billion fund would go toward long-term water savings and conservation, like helping the West’s farmers install drip irrigation systems, which use less water.

“When you consider how much you’re getting for different kinds of programs, that actually starts to add up to real significant amounts of water,” Kelly said. “One thing is clear. Putting that $4 billion into the Inflation Reduction Act for the immediate needs of this crisis is a game changer.”

[ad_2]

Source link