Abortion access in Europe isn’t universal. This network helps people receive care in the Netherlands

[ad_1]

Editor’s Note: Editor’s Note: This story is part of As Equals, CNN’s ongoing series on gender inequality. For information about how the series is funded and more, check out our FAQs.

Amsterdam, the Netherlands

CNN

—

It’s early evening in an affluent neighborhood in the Dutch city of Haarlem and bed and breakfast owners Arnoud and Marika are waiting for their next guest to arrive. They’ve prepared their single room for her, a brightly colored space with massive windows overlooking a leafy drive.

The traveller is a woman from France. She’s only staying one night, but her hosts want her to feel at home because she’s not here on vacation. She’s come to have a second-trimester abortion.

The Netherlands is one of just a few countries in Europe where access to abortion is possible past 12 weeks of pregnancy, and Arnoud and Marika’s guest is one of around 3,000 people from abroad who have accessed one annually in recent years.

Here, abortions for non-Dutch residents can be carried out until 22 weeks, according to Dutch abortion providers, and nationals can access terminations up to 24 weeks.

In the United Kingdom (with the exception of Northern Ireland), it’s possible for anyone to get an abortion until 24 weeks, and for a very limited set of circumstances afterwards, however Brexit has made it increasingly more difficult for people to travel there. And in Spain, abortions past 14 weeks of pregnancy are only legal under extremely limited circumstances, although abortion rights groups say the law is often interpreted loosely.

The restrictions mean that, for many in their second trimester, the Netherlands is their last chance to access a safe abortion. By opening up their home, Arnoud and Marika have become part of a grassroots network of people helping to facilitate that access.

“This is a house without taboos,” Arnoud told CNN. Arnoud and Marika are pseudonyms that CNN agreed to use over concerns that the couple’s B&B – which is also where they live – will be targeted by anti-abortion protesters.

Now in their 70s, the retired pair have made it their mission to be a welcoming point of entry for the people they host, many of whom they receive bleary eyed from a long day or more of travel, punctuated by weeks of anxiety and stress leading up to the journey.

“They are so relieved, they have made this terrible journey, and they come in and they’re crying,” Marika said. “I love to be a light for them.”

Since they opened their B&B seven years ago, Arnoud and Marika say they have hosted around 350 people seeking abortion care from across Europe. They explain that some came alone, others were joined by partners or friends, while some brought their family.

At first, the majority of their guests came from France and Germany, where abortion is available until 14 and 12 weeks of pregnancy, respectively. (France extended that time limit from 12 to 14 weeks earlier this year.) They say they have also hosted a number of women from other European countries including Belgium and Luxembourg, and Romania. One woman traveled from as far as the Caribbean island of Martinique, they said.

But in recent years data shows the demographics have changed, with an influx of people now traveling to the Netherlands from Poland, after the country’s highest court further tightened its abortion laws – which were already among the strictest in Europe.

The numbers coming to the Netherlands from Poland have swelled further as Ukrainians displaced there due to the war find they need to seek safe abortion access beyond Polish borders.

In October 2020, Poland’s Constitutional Tribunal banned virtually all abortions, allowing them only in circumstances where the pregnancy was a result of rape or incest, or if the pregnant person’s life was at risk. The law came into effect the following January. Prior to this, abortions were also allowed in the case of fetal abnormalities – which accounted for approximately 97% of all known legal terminations carried out in Poland in 2019, according to data from the Polish Ministry of Health.

The change in the law has left many people in Poland without legal access to safe terminations in their own country, and has created an even more hostile environment for abortion rights activists and those seeking abortions.

When asked about the worsening climate for those seeking or providing abortions in Poland, a statement provided to CNN by the Polish government simply reiterated the law, saying: “In the event of a situation that threatens the life or health of a pregnant woman (e.g. suspected infection of the uterine cavity, hemorrhage, etc.) …it is lawful to terminate a pregnancy immediately.”

“The decision whether there are circumstances in which the pregnancy threatens the life or health of the pregnant woman is and can only be made by a doctor in a specific case,” the statement added.

But abortion rights activists say the law has created a chilling effect on healthcare providers, with some doctors appearing more fearful of potential repercussions that include prosecution than doing everything they can to save a pregnant person’s life. Three pregnant women have died in Polish hospitals after being denied an abortion since the court decision, according to Abortion Support Network, a UK-based organization that helps people in Poland obtain abortion care as part of the Abortion Without Borders (AWB) network.

AWB was formed in response to the Polish government’s long standing proposals to ban abortion in 2019.

The grassroots feminist network is made up of six organizations from Poland, the UK, Germany and the Netherlands. They say the Polish state is failing women and have made it their mission to ensure safe access to abortion for any reason a person chooses to have one – including whether the pregnancy is wanted or not.

“We don’t want to make you feel like you have to explain yourself, and that you have to earn your abortion with a sob story,” said Polish abortion rights activist Kasia Roszak.

Roszak, who now lives in Amsterdam where she works with Abortion Network Amsterdam (part of AWB), says she knows exactly how it feels to not have agency over her reproductive rights, which is one of the reasons she works to ensure access for anyone globally who needs it.

“We believe that abortions are part of life. It can be an empowering, positive experience. And if it’s not, if it’s something hard for you, then we’re going to give you space and validation of your feelings,” Roszak said. “I feel like it’s my responsibility to be able to share with people that there are options.”

From December 2020 to December 2021, AWB says they helped 32,000 people from Poland access abortions across Europe – an almost six-fold increase from the previous year.

In 2021, the network says they facilitated travel for 1,186 people in Poland – more than quadruple the number of people they supported with travel in 2020. More than half of those people travelled to the Netherlands, making up 52% of the total they helped to visit the country for abortions that year, according to AWB.

Official 2021 data from the Dutch government shows 651 people from Poland had abortions in the Netherlands, more than double the number of people in 2020.

“Effectively, we took over all [of Poland’s] fetal anomaly cases,” said Roszak. Numbers previously hovered around 1,000 cases a year in Poland, according to government data.

The network gets connected with people who need their help through a process like this: A person with an unwanted pregnancy will first call a hotline in Poland, where they have two options, depending on how far along they are: take pills or travel for a procedure.

If they are less than 12 weeks pregnant, they are sent the abortion pills mifepristone and misoprostol – approved by the World Health Organization – to take in the privacy of their own home. This is the case for the majority of the people who reach out to them, according to AWB data.

However, for people whose pregnancies have already passed the 12-week mark, they will likely need to travel to a clinic abroad. This is also the case for those living in other European countries where laws prohibit abortions after the first trimester. For these people, the network taps into its web of volunteers and activists who will work around the clock to arrange appointments at clinics, translate documentation and provide financial assistance to help meet the cost of the procedure and related travel.

Second trimester abortions may be available in the Netherlands but they are expensive for non-Dutch residents, costing up to 1,100 euros (roughly $1,100) for the surgical procedure which typically takes no longer than 20 minutes. Counselling, preparation for the procedure and recovery however require the better part of a day.

Depending on each individual circumstance, assistance arrives in many ways and AWB may cover all or part of the costs, which can include flights, accommodation, and handling appointments with the treatment center directly.

Money is raised mostly from private donations, according to activists within the AWB network, but some of the organizations within it are supported by big donors. Without financial assistance, abortion travel is especially prohibitive for working-class people, migrants and others living in poverty.

Kinga Jelińska, Executive Director of the Amsterdam-based group Women Help Women – which is also part of AWB – told CNN: “We return abortion back to common people, no matter the law, no matter the stigma, no matter the cost.”

Second-trimester abortions constitute a relatively small proportion of the total number of officially recorded abortions in high-income countries. The vast majority are carried out in the first trimester.

Those seeking second-trimester abortions do so for a number of reasons, including not having previously realized they were pregnant; a change in personal circumstances such as financial difficulties or the breakdown of a relationship; unexpected medical problems in themselves or the fetus, and trauma surrounding rape and sexual abuse cases, which can also be a reason that one might not recognize the pregnancy until it is too late to access an abortion in their country.

“People sometimes think that it’s a matter of fundamental principles and beliefs. [But]we see day after day, people coming to us and saying… ‘I used to be against abortion, but my situation is different,’ Jelińska explained.”The decision whether to continue the pregnancy or not, is highly contextual.”

At the Bloemenhove clinic in Haarlem, one of two clinics in the country that offer abortions past 18 weeks, the parking lot looks “like the United Nations,” Roszak quipped, referencing the fact that car registration plates can be seen from all over Europe.

The clinic, a bright and modern space with a peaceful garden area, treats approximately 15 people a day, 4 days a week, according to its director, Femke van Straaten. But the influx of Polish patients has, van Straaten said, led to a shift in the way that her team works.

Prior to the Polish court ruling, more than half of the patients at Bloemenhove were Dutch and most came to terminate unwanted pregnancies, van Straaten explained. As such, staff were able to recommend in-country aftercare, including counseling resources.

Now, with more patients coming to the clinic from Poland with wanted pregnancies (many of whom came for terminations due to fetal abnormalities), they have “different needs for care,” said van Straaten.

One of the ways the clinic responded was to establish a memorial at a local cemetery for women to find some closure for their unviable pregnancies.

“They couldn’t take their child back home, and they had no place for their grievance,” said van Straaten, who helped organize the memorial last year at the suggestion of the Polish abortion rights network. She added that memorial services are also available for people carrying viable fetuses who chose to terminate their pregnancies.

As part of this aftercare, patients can opt for a cremation and are permitted to take the ashes home. For those who can’t wait for cremation, the cemetery offers to scatter the ashes on the site, where a steel tree has been erected and babies’ names are engraved onto a rainbow of leaves that hang on its branches.

Dr. Elles Garcia, an abortion care provider at Bloemenhove since 2016, works to assuage concerns that some people – particularly those from Poland – have about returning home after their termination.

“They often ask me the question: ‘What do I tell my gynaecologist? Can I tell them that I had a miscarriage?’ They’re so afraid of getting back to their doctor in their own country and to tell them the truth – they can’t,” she said from one of the clinic’s consultation rooms.

Garcia said that while she assures patients that medically, their doctors back at home won’t be able to know whether they had a miscarriage or an abortion, she still encourages them to be honest about what they went through, not only for themselves, but in hopes it might start to break down societal taboos.

“I tell them to say that you were here for an abortion, because here it’s legal – you can tell them the truth,” she said, before acknowledging, “but then they get afraid and anxious.”

To help people prepare to return to a society where abortion is both restricted and taboo, the AWB Polish helpline has also expanded its remit to provide aftercare, including psychological counseling for those in need.

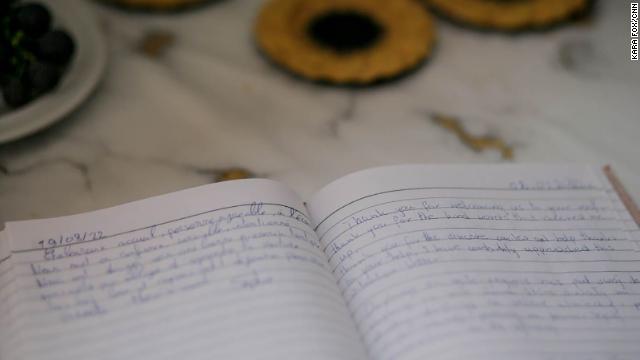

Back at their B&B, Arnoud and Marika are reflecting on the past several years of providing hospitality to people at a difficult time in their lives.

Only around a third of their guests stay for two nights, they say, the majority return to their countries of origin straight from the clinic. And so the relationships are fleeting, but the septuagenarians know their impact can be profound. They see their job as being to listen and reassure.

“People come from the room and ask: ‘Can we talk to each other?’ said Arnoud, explaining that guests often gather around their dining room table or sit in their garden for a chat if they stay the second night.

The couple say that while they were never planning on becoming a hub for abortion travel when they first decided to open their business, they can’t imagine their B&B in any other way.

But unlike most business owners, they say they relish the day when their business might go bust.

“When the law changes in France, like we have in Holland, when the law changes in Poland, like we have here, it will be better – I will sing a song,” Arnoud said.

He looks to Marika and adds: “Our business is not important. It’s more important that women can decide for themselves … that’s the most important.”

[ad_2]

Source link