Abby Choi: What the death and dismemberment of an influencer says about life in ‘safe’ Hong Kong

[ad_1]

Content warning: This story contains descriptions of violence that readers may find disturbing.

Hong Kong

CNN

—

The postcard image of Hong Kong is one of glitzy skyscrapers against lush mountains, dim sum restaurants and investment bankers in suits.

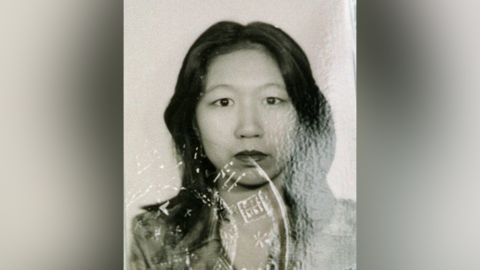

But in recent weeks, the international financial hub has again been in the headlines for something darker: the death of model and influencer Abby Choi, whose dismembered body parts were found along with a meat slicer and electric saw in a rental unit last month.

The death of the 28-year-old mother has not only horrified a city regularly ranked as one of the world’s safest, but gripped much of the world’s media with the grisly details of her alleged killing.

For Hong Kongers, it has also resurfaced painful memories of previous cases of dismemberment in the city – many targeting young women and almost all perpetrated by men.

There’s the so-called “Hello Kitty” murder of 1999, when 23-year-old Fan Man-yee was abducted by gang members and brutally tortured for a month before her death and dismemberment. Her skull was eventually found sewn inside a Hello Kitty plush doll.

There were the four women, the youngest only 17 years old, killed by a taxi driver who kept their dismembered body parts in jars before his arrest in 1982. Then came 16-year-old Wong Ka-mui, who was strangled and dismembered in 2008 and her remains flushed down a toilet.

And in 2013, Glory Chau and Moon Siu were murdered and dismembered by their 28-year-old son, a crime described by the judge as “evil” and “absolutely hideous.”

Reams of headlines followed each murder. But for all the media attention, experts point out such cases are exceptionally rare in Hong Kong, a city with an incredibly low rate of violent crime for its population of 7.4 million.

Hong Kong sees only a few dozen homicides each year, compared to several hundred in New York. And it recorded only 77 robberies last year – compared to more than 17,000 in New York and 24,000 in London.

So why the huge interest in these previous few cases? Their rarity, combined with their brutality, is one factor, experts say.

But there may be another at play: That buried beneath all the grim details of death is a peculiar insight into living in one of the world’s most densely populated cities.

Roderic Broadhurst, an emeritus professor of criminology at Australian National University previously based in Hong Kong, where he founded the Hong Kong Centre for Criminology, estimated there had been a dozen or so dismemberment cases in the city over the past 50 years.

Philip Beh, a semi-retired forensic pathologist who has previously worked with the Hong Kong police, gave a slightly lower estimate, saying he could recall fewer than 10 such cases in his 40-year career.

Both experts emphasized that Hong Kong is still very safe, and that these numbers are relatively low. Indeed, Hong Kong’s reputation for safety meant the few cases that did occur left a stronger “imprint” on the city, Broadhurst said.

But both also suggested the gruesome nature of these past cases – in particular, the dismembering of limbs – reflect the realities of life in Hong Kong.

Simply put, it is much harder to hide a body in the tightly packed city, home to tiny apartments and some of the world’s most densely populated neighborhoods.

Someone trying to dispose of a body in rural areas of Australia, Canada or the United States has “a very good chance of getting away with it,” thanks to the ample space and open terrain, Beh said.

Not so in Hong Kong.

“These are essentially people who are trying to get away with a crime, but failing to do so,” said Beh.

A killer in Hong Kong more likely than not will live within just a few feet of dozens of people who could spot them trying to dispose of a corpse – prompting some to break victims into smaller parts for disposal.

“Most people live in apartment blocks on top of each other. We don’t have individuals with houses and gardens where you can go out and dig a hole and try to bury a body,” Beh said. “You’re never really alone; your neighbors are above you, below you, next to you. Anything out of the ordinary will catch someone’s attention.”

Broadhurst agreed, pointing out that in apartment buildings, a murderer might have to get into an elevator shared by more than 100 households just to go outside.

Several previous cases have involved killers who cooked or boiled body parts – details that have horrified the public, and likely fueled by unsubstantiated rumors surrounding cases like the 1985 “pork bun murders” in neighboring Macao. A man killed a family of 10 including the owners of a restaurant, and – as the urban legend (and the movie it inspired) goes – supposedly served them up in buns.

But the explanation is far more mundane in most cases, Beh said.

In Hong Kong’s subtropical, humid climate, “the smell of the body very quickly captures attention,” he said – hence why some murderers might attempt to remove the smell by cooking dismembered parts.

As for why these killers didn’t use methods commonly seen in other countries – keeping the body in the freezer, dumping them in the water late at night – Hong Kong’s density poses yet another difficulty.

In its notoriously expensive housing market, apartments are usually too small and cramped for large furniture or kitchen appliances.

“Very few individuals have large refrigerators at home,” Beh said. “Even fewer have freezers. You can’t even keep the body if you wanted to.”

He added that the same scarcity applies to cars – and thus the same difficulty in discreetly transporting a body.

Few residents own vehicles since buildings with places to park are at a premium – in 2019, a parking space sold for nearly $1 million dollars, a record – and the city has an extensive, efficient public transit system anyway.

These combined factors could explain various cases over the years where killers used bizarre, grotesque methods to deal with their victims’ bodies – such as the woman murdered by her husband in 2018 and her body kept in a suitcase, or the 28-year-old man whose body was found in a block of cement in 2016.

“We live in a place where essentially, if you have killed someone, your next very pressing question is: What do you do with the body?” Beh said.

“There are very few options.”

[ad_2]

Source link